Mere Christianity (C.S. Lewis) 02 - Preface

Preface

Background of the Book's Publication

The content included in this book was originally presented as a series of radio broadcasts, which were later published in three separate volumes: Broadcast Talks (1942), Christian Behaviour (1943), and Beyond Personality (1944).

C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity originated from a series of BBC radio broadcasts during World War II. Amid the chaos of war, the BBC sought to offer moral encouragement and spiritual guidance to the public through a Christian lecture series, and Lewis—an Oxford scholar and former atheist—was chosen to present it. He approached the topic with logical clarity and human warmth, framing the talks in a way that embraced not only Christians but also skeptics and non-believers.

The broadcasts aired between 1941 and 1944 in four installments, covering topics such as moral law, Christian beliefs, Christian behavior, and the Trinity. These talks were first published as three separate books: Broadcast Talks (1942), Christian Behaviour (1943), and Beyond Personality (1944). Lewis later revised and integrated them into a single coherent work, published in 1952 as Mere Christianity.

Avoiding Controversy and Theological Disputes

Lewis stated that his highest and only service was to "explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times." To do this, he believed it was necessary to avoid religious controversies and theological disputes, and he gave three reasons for that position.

- Doctrinal or historical disputes that divide Christians should be left to experts, not addressed by laypeople.

- These controversies do not help non-believers come to faith.

- There are already many scholars dealing with such complex issues.

For Lewis, the best way he could serve was by clarifying and preserving the shared, ancient beliefs of Christians—a task he chose to fulfill through his radio talks and this book. His approach offers much insight even today.

Though a member of the Anglican Church, Lewis was a Christian apologist, not merely a Protestant one. An apologist is someone who defends and explains faith or belief through rational argument and reasoning. Importantly, Lewis did not represent one denomination but spoke broadly to all Christians. The term Christian encompasses Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Protestantism, Anglicanism and others.

Jesus saith unto him, If I will that he tarry till I come, what [is that] to thee? follow thou me. [John 21:22]

Jesus’s answer to Peter suggests: "Don’t worry about others—just follow me." It also implies: "Don’t get lost in speculation or doctrinal arguments. Live out what I taught you."

A note of caution toward Roman Catholicism is also discernible.

To a thoroughgoing Protestant, the beliefs of the Roman Catholic Church threaten the clear distinction between Creator and creature—a divide that cannot be bridged no matter how holy the creature becomes. It feels like a revival of polytheism. As such, it’s difficult for Protestants not to see Catholics not merely as opponents but almost as idolaters. The topic of the Virgin Mary, therefore, is one that could completely ruin a book like this for those who struggle to accept the divinity of her Son.

Religious and doctrinal conflicts have taken countless lives throughout history. One of the most tragic and absurd examples may be the Old Believers Persecution in Russia.

In the mid-17th century, Patriarch Nikon of the Russian Orthodox Church initiated reforms aligning liturgical practices more closely with those of the Greek Orthodox Church. Among the changes was repeating “Alleluia” three times instead of twice. Traditionalists who resisted were called “Old Believers.” Branded as heretics, they were imprisoned, tortured, burned, or driven to mass suicide. A small difference in ritual escalated into violent suppression and martyrdom.

Silence in Part III on Certain Moral Topics

Ever since I served as an infantryman in World War I, I’ve harbored a deep dislike for people who sit safely at home and lecture those at the front. That’s why I hesitate to speak on temptations I haven’t personally faced. Not everyone experiences every kind of temptation. I don’t feel qualified to take a firm stance on pain or sacrifice I haven’t endured. Nor do I have the pastoral duty to do so.

It seems to me that Lewis maintained a keen insight alongside a precise and delicate attitude. He appeared to be someone deeply wary of the common errors often committed by those in positions of power or authority. This caution is evident in his discussion of the historical and social evolution of the word “gentleman.” Originally, it referred to someone who wore a coat embroidered with a family crest and owned considerable land. Later, however, it came to mean a man of neat appearance and courteous manners—or, in many cases, simply someone the speaker personally found likable. Lewis uses this example to highlight the danger of pride that can creep into the definition of the word “Christian.”

If we allow the word Christian to be used in a purely refined or specialized sense, the term becomes practically useless. Christians themselves won’t be able to use it meaningfully to refer to others. We can’t judge who is closest to Christ in the deepest sense—that’s beyond our knowledge and authority. To do so would be an act of pride.

Originally, Christian referred to those who accepted the apostles’ teaching—the disciples—and the term was first used in Antioch. However, Lewis critiques the modern use of the word, where it often implies a morally superior person. This turns the word into a tool for judgment and social distinction—perhaps a veiled critique of British society at the time.

For me, the central issue was not the word’s historical evolution but the spiritual danger of pride. Those who think of themselves as especially moral, righteous, or faithful are most prone to fall into this error. In Christian terms, pride stands opposed to humility and meekness. Lewis, I believe, was more concerned with guarding against this spiritual pride than with terminology itself.

"Mere" Christianity as the Hallway

One of the most striking passages appears at the end of the preface:

What I’m trying to do is lead people into the hallway from which all the rooms open. If I can bring anyone into the hallway, I’ve done my job. But it is in the rooms—where there is firelight, chairs, and food—that one must finally live. The hallway is a place to wait, to explore, not a place to settle. While you’re in the hallway, follow the rules common to the whole house. And when you find your room, be kind to those in other rooms or still in the hallway. If they’re mistaken, they need your prayers all the more.

Curious!

This long, 15-page preface left me with a question:

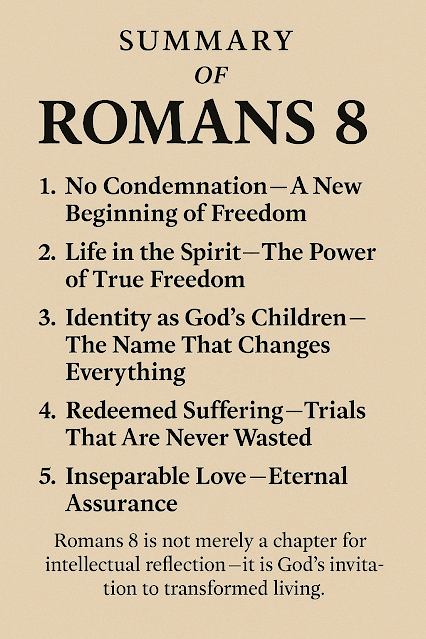

The concept of “mere” Christianity, I felt, refers to “the shared belief held by nearly all Christians throughout the ages”—the essential core of the faith that every Christian ought to know, regardless of denomination or doctrine.

Shouldn’t that be what we’re truly curious about?

Comments

Post a Comment